Life in a Inquiry Driven, Technology-Embedded, Connected Classroom: Science

I teach in an inquiry, project-based, technology embedded classroom. A mouthful, I know. So what does that mean? It means I lecture less, and my students explore more. It means that I create a classroom where students encounter concepts, via labs and other methods, before they necessarily understand all the specifics of what is happening.

It’s a place where my students spend time piecing together what they have learned, critically evaluating its larger purpose, and reflecting on their own learning.

It also means my students don’t acquire knowledge just for the sake of acquiring it. They need to do something with it — that’s where “project-based” comes into play. Finally, technology is embedded into the structure of all we do. It’s part of how we research, how we capture information, and how we display our learning. It’s never an accessory tacked on at the end.

into play. Finally, technology is embedded into the structure of all we do. It’s part of how we research, how we capture information, and how we display our learning. It’s never an accessory tacked on at the end.

into play. Finally, technology is embedded into the structure of all we do. It’s part of how we research, how we capture information, and how we display our learning. It’s never an accessory tacked on at the end.

into play. Finally, technology is embedded into the structure of all we do. It’s part of how we research, how we capture information, and how we display our learning. It’s never an accessory tacked on at the end.So what does this look like?

On lab days, one of the first things my students do is take out their phones. Our school has a cell phone policy that normally bans these devices during class time; however, we have permission to use them in learning situations. I even lend my phone to groups who may not have one.

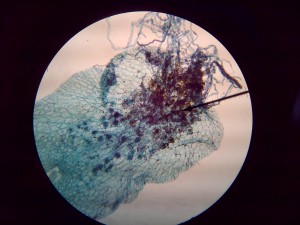

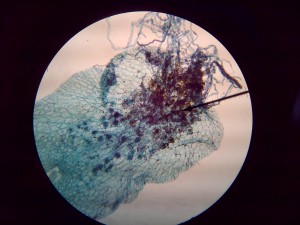

I used to have students sketch pictures of lab slides. The truth is most of them didn’t look anything like what was on the slide. I doubt our students have spent much time sketching throughout their schooling career. If they have, they’re not very good at it! In the end, they mostly look like a mass of circles.

much time sketching throughout their schooling career. If they have, they’re not very good at it! In the end, they mostly look like a mass of circles.

much time sketching throughout their schooling career. If they have, they’re not very good at it! In the end, they mostly look like a mass of circles.

much time sketching throughout their schooling career. If they have, they’re not very good at it! In the end, they mostly look like a mass of circles.

Last year, instead of sketching, my students began taking pictures with their phones of what was on the slide. These are then uploaded to our wiki and become part of our digital textbook. The beauty of this is that students who have missed the lab can refer to them. We also do this for dissections. Within minutes, they’ve often uploaded these pictures to Facebook.

Do my students use their phones during this time for non-educational tasks? Probably. But until I see they’re not focused on their work, I’m not prepared to be the texting police. Instead, my students know they are trusted and they need to act accordingly.

The nuts & bolts of embedded technology

My students have multiple options as to the final format of their lab submission. Some students choose to hand in paper labs, but a number have started creating v-labs. These are labs in the form of Voicethreads or videos. Sometimes their paper labs simply include the pictures. I also receive labs that are created in Google Docs.

Other times we’ll learn content in the classroom, but we do it interactively. How? We Google Jockey. The first time I told my students we were going to Google Jockey, they didn’t believe it was an actual term. I told them to Google it. It is.

I facilitate the discussion by asking questions, while my students Google, looking for the information we need. As they come across links and videos that explain what we’re learning about, my students send me links that I add to our wiki. This process allows us to talk about the information, including how to research & find reputable information.

If I had a set of laptops or iPads on which my students could reliably create a Google Doc of our notes as I speak or they Google jockey, I would do it that way instead. There’s something engaging about creating a real-time set of class notes. Unfortunately, the technology available at my school doesn’t allow for it. Our Mac lab is incredibly unreliable, only letting a few students into a Google doc at a time.

This past week in Chemistry, my students have been learning how to name chemical compounds, a process that is laden with rules and often difficult to learn. Yet knowing the process is essential for correct chemical nomenclature. I’ve created a livescribe of the process my students need to use. We’ve also discussed it in class. For three days, my students have been trying to engrave this process into their synapses, through repeated practice. There are a number of activities on our wiki that my students can engage in during class. The can learn polyatomic ions, how to transfer formulas to names, or names to formulas, and they can practice naming acids — to name a few. This format allows students to choose what they work on. And it allows me to talk to every student, every day.

This past week in Chemistry, my students have been learning how to name chemical compounds, a process that is laden with rules and often difficult to learn. Yet knowing the process is essential for correct chemical nomenclature. I’ve created a livescribe of the process my students need to use. We’ve also discussed it in class. For three days, my students have been trying to engrave this process into their synapses, through repeated practice. There are a number of activities on our wiki that my students can engage in during class. The can learn polyatomic ions, how to transfer formulas to names, or names to formulas, and they can practice naming acids — to name a few. This format allows students to choose what they work on. And it allows me to talk to every student, every day.Formative assessments to guide learning

Usually, my motto is Einstein’s — “Never memorize anything you can look up.” However, chemists have a particular language. You need to understand it, including the vocabulary, before you can do something with it. Almost every morning, before we start, my students have a small quiz, a formative assessment. It doesn’t count for marks, instead the assessment is used by my students. Rather than penalizing them for what they haven’t mastered yet, it shows them, and me, what we need to work on. As they become more proficient, they become more confident about their abilities.

Next week, in Biology, my students are learning about DNA. To begin, they will perform a lab where they extract and spool DNA from a cow liver. While they’ll be able to see it, they really have no idea of its structure or composition. For the next few days, my students will research the basics of DNA, and, in pairs, create Glogsters.

I love using a format like this because it easily differentiates instruction for a classroom that is full of different abilities and learning styles. Students can create a Glogster that best suits their learning needs. Additionally, I have students who might read at a grade 3 or 4 level. These students refer to digital resources that I have hand-picked and linked to on our wiki. With help, they are able to create their own Glogsters that are perfect for their learning and reading level. Technology allows students to adapt instruction in way that was never possible with print materials.

I love using a format like this because it easily differentiates instruction for a classroom that is full of different abilities and learning styles. Students can create a Glogster that best suits their learning needs. Additionally, I have students who might read at a grade 3 or 4 level. These students refer to digital resources that I have hand-picked and linked to on our wiki. With help, they are able to create their own Glogsters that are perfect for their learning and reading level. Technology allows students to adapt instruction in way that was never possible with print materials.

Once my students have gleaned the basics, we’ll create models of DNA and engage in a number labs that show my students how DNA is used in crime scene analysis.

My students are also working on an independent genetics project. They can research anything in the realm of genetics that deeply interests them: cloning, crime scene analysis, genetic research, stem cell research, the list goes on. In order to check that their project is not too large, my students have one week to submit their project proposal, which outlines their topic, how they will research their project, and what format the product will look like. They can build a model, create an interactive presentation that includes a lab, or create a digital product using a tool such as Prezi, Flip Snack, Empressr, Wix, My Brain Shark, or create a screencast, to name a few. The only stipulation is that they cannot hand in a research report or a powerpoint. Their digital products will then be published on our wiki.

The powerpoint rule is flexible. This morning one of my students said to me: “I’m going to do my project on Dr. Burznski and his work with anti-neoplastons and their anti-cancer effects. My product will be a PowerPoint presentation, which I will then upload into ‘myBrainShark’ and create a voiceover.” I stood stunned for a moment. Did all of those words really come out of the mouth of a grade 11 student?

Finally, to keep track of housekeeping items, and remind students of upcoming due dates, my favourite tool is Remind 101. And my students love it! Essentially, I set up the class, my students send a text or email to the class site, and every time I enter a message, it is sent to them via text or email. I can even set up reminders in advance.

Teaching then and now

Before the technology/constructivist shift in my classsroom, I would have taught all of this quite traditionally. We’d learn formulas through worksheets. I’d lecture a lot, with supplemental textbook readings here and there. The whole design would have been extremely teacher centered. And at the end of it all, I’d hope they learned something about Chemistry & Biology.

Instead, inquiry and technology are a natural part of our science classes. It’s what my students have come to expect. Instead, of saying, “hand in your assignments,” I say, “publish your assignments and send me the link.” That’s the 21st century difference.

Images: Shelley Wright

No comments:

Post a Comment